On the 1st of August 2024, the École de Parachutisme Sportif de Vannes Bretagne organised a parachute drop for 14. The sky diving centre is a non-profit operating their aircraft under AIR OPS.

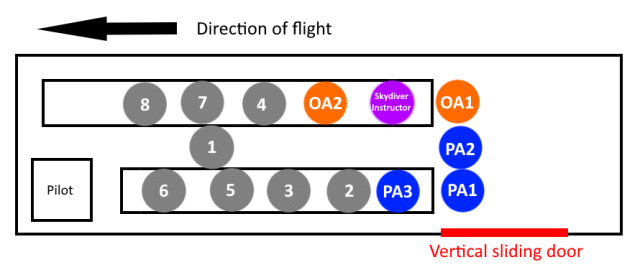

The aircraft was a Cessna 208 Caravan, a single-engine turboprop, registered in France as F-HVPC and owned by the sky diving centre. It was configured for sky diving, with two benches, one of which seats five sky divers and the second seven.

Up to three sky divers can sit on the floor between the benches or by the door, for a maximum of 15 sky divers.

Each parachute system included a harness, a reserve (backup) parachute, the main parachute and an automatic safety device designed to deploy the reserve as needed. The parachutes are connected to their harnesses through risers: webbing straps that group the suspension lines.

When jumping from the aircraft, the sky diver pulls out the handle and releases it, causing the small pilot chute to slip out of a fabric pouch on the back of the harness. The pilot chute catches air which initiates the deployment of the main canopy.

The parachutes had been inspected four months before the jump, 4 April 2024, with the reserve repacked by a certified packer and valid until 4th April 2025.

For the flight that day, there were two jumps planned around 1,200 metres and 4,000 metres. (~4,000 feet and 13,000 feet).

At 1,200 metres, the first jumpers were three experienced sky divers practising precision landing and two students under the supervision of the sky diving instructor. Then at 4,000 metres, the remaining sky divers and the instructor would jump together.

The sky divers carried out their equipment checks on the ground before boarding and would repeat them during the climb before reaching jump altitude. The deployment handles for the main canopy, reserve canopy, and cutaway can easily become dislodged from their housings with minimal movement.

The instructor was responsible for checking the equipment of the two students, which he did. He held C and D licences, allowing him to supervise other sky divers and perform demonstration jumps. He was in training for the federal instructor rating.

The pilot held a commercial licence with 6,600 flight hours, with 5,500 as a sky diving pilot.

It was a hot August day, 28-30°C (82-86°F) and it would have been sweltering in the cabin. They departed Vannes and climbed away, ready for their jumps.

The sky divers were sitting according to their jumps, with the eight sky divers jumping second seated nearest the cockpit, with one on the floor between the benches. The sky diving instructor sat at the end of the longer bench, with one student on the bench to the instructor’s left and one student to the right of the bench, sitting on the floor. The three experienced sky divers practising precision landings were nearest the door, with one on the short bench and two on the floor. The three sky divers on the floor (one student, two precision) sat shoulder to shoulder. Everyone was sitting with their backs to the cockpit.

The aft door was a vertical sliding design of Plexiglas slats. The Cessna 208 was certified to fly with the door open as a part of its sky diver operations. The only restriction was that the door should remain closed during take off and below 500 metres, so that occupants could not fall out at a height too low for the canopy to deploy. The head of the sky diving centre confirmed that it was standard for the sky divers to partially open the door for some fresh air when temperatures were high, in order to cool down the cabin. There had never been any issue with partially opening the door. The pilot had explicitly given permission for this before the flight.

The sky diver sitting on the floor closest to the door had been assigned the task of operating the aircraft’s vertical sliding door. He was very experienced: he held C and D licences and also a federal instructor rating with 3,600 jumps logged. He had attended a briefing before the flight to learn about the door and the precautions to take when operating it. The pilot had told him that he could partially open the door during the climb in order to ventilate the cabin.

It was very hot in the cabin. After checking for any anomalies, the sky diver raised the slats a bit to ventilate the cabin. He opened the door by about ten centimetres (4 inches) to let the air in, slightly less than the height of a soda can.

The instructor, seated at the end of the bench furthest from the door, started to check his students’ parachutes. He started with his student sitting on the floor. The more experienced sky diver sitting next to him on the floor shifted towards the door to give the student some room.

The sky diver sitting by the door positioned his foot to act as a door stop. He felt the sky diver in the middle shift towards the door and press against him. He didn’t move but turned his chest to the right and leaned a bit out of the way.

In the process, he must have squashed the leather ball of the pilot chute between the parachute and the floor. What no one realised was that a bit of his pilot chute had come out of the fabric pouch.

The slipstream from the open door caught the chute and yanked it out of the aircraft. This triggered the main container to open, the start of the sequence to deploy the main canopy.

The sky diver sitting on the bench heard something from the door. He turned to look and saw the pilot chute of the sky diver nearest the door fly out of the aircraft. The main canopy container of the parachute was open and being dragged outside. He grabbed the suspension lines but he couldn’t pull the container back in.

The sky diver on the floor was relentlessly pulled towards the door.

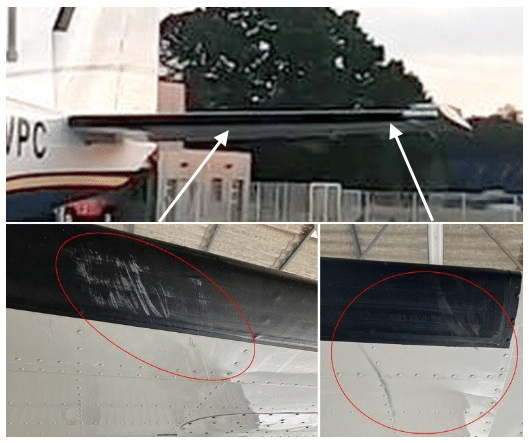

The main parachute opened outside of the aircraft under the left horizontal stabiliser, the small wing on the tail.

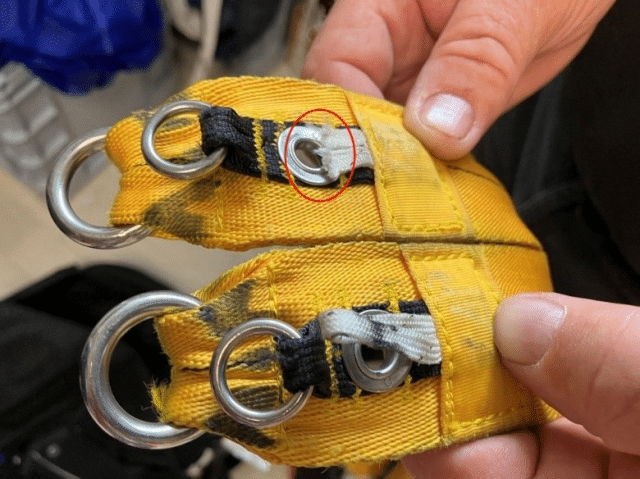

While the sky diver was being dragged out of the aircraft, the top loop of the right-hand riser snagged on the door frame and then snapped under the strain. The main canopy was now only partially connected to the harness.

The sky diver felt himself being pulled through the bottom of the door, three slats breaking under the pressure. He felt a sharp pain in his leg as he went over the threshold. He didn’t know it yet but his leg was broken.

The riser that snapped meant that the main canopy was now only partially connected to the harness. The reserve canopy deployed up and towards the tail. It rubbed against the horizontal stabiliser, enough to leave a mark, but thankfully did not get caught up in the tail.

The man sitting on the bench looked out the broken door and saw the sky diver outside of the aircraft under the reserve canopy, with the main canopy still partially connected.

From the sky diver’s point of view, he was suddenly outside of the aircraft. He quickly saw that the reserve had deployed but that the main canopy was still partially connected to the harness. He began to use the reserve canopy to control his descent while keeping the main canopy out of the way so it would not get tangled with the reserve. Meanwhile, the earth was rushing at him.

He hit the ground, hard. He broke his back, fracturing five lumbar vertebrae. All he could do was lie there and wait for someone to find him.

Meanwhile, in the cockpit, the pilot heard a loud noise. They were at about 2,000 feet, halfway to their jump altitude. His stick vibrated strongly. He wasn’t sure what was happening and thought that an elevator may have failed. He pulled back on the power and started to descend. The vibrations stopped but he decided it was better to abort the jump, as he wasn’t sure what was wrong with the aircraft.

The sky divers must have been in shock. The one on the bench said they were already descending by the time he considered saying something, so he presumed the pilot realised what had just happened.

I think it’s fair to assume that everyone was in shock.

They landed safely within a few minutes. The pilot had no idea that he had lost a passenger until he had taxied to the parking stand. He immediately called ATC to say they needed an emergency search for the sky diver.

There are no details about the search and rescue other than that the pilot told the BEA that the sky diver was “quickly found” by the rescue services.

In fact, in general, I’m disappointed by the detail in the BEA report. There are a number of angles that seem not to have been explored at all. That said, I like that the report is careful not to assign blame or second-guess anyone’s decisions. Cracking open the door to get some air into the hot cabin was authorised and the sky diver assigned to the door was experienced and properly briefed. All of the equipment checks were completed as expected.

The key here is the positioning of the sky diver. This meant that the leather pilot chute ball was almost certainly squished between the parachute and the floor. Many sky divers prefer the leather ball: it’s easier to grip and doesn’t break as easily as a plastic ball. But the leather also slides less easily, which explains why it got trapped, pulling out the pilot chute.

Further, the pilot chute pouch, on the right side of the back, was directly exposed to the slipstream. It was a sequence of events that no one had considered.

When the right riser snagged on the door frame, the textile loop securing it severed, triggering the reserve deployment, exactly as designed. It was pure luck that neither canopy caught on the horizontal stabiliser. The sky diver managed both canopies to the ground, which speaks to his experience level.

The report concludes that although the risk of a parachute snagging on the horizontal stabiliser or elevator is a known hazard of sky diving, no one had thought through the interaction of the airflow from the partially open door.

As a result of this incident, the sky diving centre no longer allows for the door to be opened during flight, not even partially, except during the drop phases.

It must get awfully hot in the cabin but that’s still better than suddenly finding out you are outside of it.